In memory of Helen: the rituals, the resilience, the love that stayed

Community, Living with MND, Personal Stories

26 June 2025

For 30 years, it was part of Helen and Keith’s daily ritual — until motor neurone disease slowly took everything away. In this moving first-person reflection, Keith Thomas shares the heartbreak, resilience, and enduring love that defined their final years together. We’re honoured to share Helen’s story as part of MND Action Month — a time to listen, reflect, and honour those affected by this cruel disease.

Introducing Helen

My dear wife’s name was Helen. She was dux equal at high school and a consummate mother of five. She played the piano and violin, sang beautifully, loved gardening and walking in the bush, and was an excellent cook, homemaker, and hostess to the many who visited and stayed. Loving and generous to all, unstinting in everything she did, she embraced travel and was always eager to explore.

We were on holiday, and she fell in a supermarket car park. She was hurt but helped by bystanders and attended by compassionate emergency nurses. I count this as the beginning of her two-year battle with motor neurone disease (MND).

She then developed foot drop — also known as drop foot — a muscular weakness that makes it difficult to lift the front part of the foot. This can be a sign of neurological, muscular, or anatomical problems. Her doctor wasn’t sure of the cause, so she was referred to a specialist. A brain scan was arranged to look for signs of a stroke or other abnormalities.

This investigation took several weeks and involved several consultations. She was also X-rayed to test for problems in one of her knees, as there had been some previous evidence of difficulties. There was evidence of degeneration and osteoarthritis, and she was placed on an exercise regimen under the supervision of a hospital physiotherapist. We purchased an Exercycle.

For those suffering from the early effects of MND, these consultations and continuous visits can be very taxing. Getting Helen into our car was hard, and every outing was difficult. Early diagnosis would be a boon.

A diagnosis we didn’t expect

Finally, after more appointments, the original specialist referred her to Neurology. The test was simple, and the immediate diagnosis was “suspected ALS (the most common form of MND).” The next day, it was confirmed that she had MND.

We cried.

Before this, there had always been some degree of hope that somehow the situation would improve. Now, we had no hope. There was a drug which may slow the progress of the disease, not a solution, but only a possible way of extending her life. There was also the question of whether to install a tube to allow feeding without the danger of choking.

She was tested to see if she could take advantage of these options, but did not pass the tests.

Finally, we were on our own. The exercise regime was cancelled, and we were to receive professional help as problems were identified. Of course, there were many problems, and I have nothing but praise for the assistance we received from dedicated workers.

Living with MND

The hospital gave us a four-wheel walker to allow Helen to navigate on her own around the house, and when we went out. It was a disaster. We went to a hospital appointment and started along the corridors. Suddenly, she was on her knees. The walker had become unbalanced and had run away from her.

The idea, in those circumstances, is to apply the brakes. But Helen couldn't do that quickly, if at all, as her hands were weak and slow. She fell. This was trauma heaped upon trauma and speaks powerfully to the emotional pressure that builds upon everyone when dealing with the reality of MND. This emotional stress is very real and has to be handled by those who are caring; otherwise, it would become overwhelming to the point where we would become ineffective.

We purchased a two-wheel walker with rubber stoppers on the back legs, which proved much safer — the stoppers helped prevent it from running away. But as the disease progressed, we soon had to abandon any attempt to keep her walking. From then on, we moved her by wheelchair.

At this point, our sons and sons-in-law built a ramp to our front door to avoid negotiating steps. Family support was crucial in this journey. I cannot imagine how things would have turned out were it not for their support.

She was having difficulty playing the piano, even simple tunes. She couldn’t negotiate the stairs, so the computer she still used was reinstalled on the ground floor. She began to lose her speaking ability, and singing was beyond her ability.

These were heartbreaking events for her, for me and the family. I am sure that in some MND situations, the pressure, the anguish, and the ever-present question of “why” could be too much. It was, almost, for us.

Coping is an important skill. You cannot dwell on these developments, on the increasing debilitation. You have to understand the inevitability of the disease's progression, yet treat each development as another difficulty to address and overcome the best way you can. MND doesn’t care, but you can meet each setback with a new plan, a new brightness, and make the very best of the situation. Failure here can lead to despair.

The life of your loved one was beautiful. So much was given, so much love and dedication. You are now overcoming in the face of this adversity. You both are winning because you are extracting the best from every situation. You are functional, you are coping because you are both dedicated to the goal.

It may be that the disease also affects the brain and cognition. With Helen, this was a factor and one that is difficult to deal with as a different person emerges. Fortunately, her episodes were of small duration before returning to “normal.” We had to remind ourselves that this was not our wife, our mother, but another product of a cruel disease.

Showering in a typical house and using a shower chair is difficult. Our bathroom was not designed to allow a large, wheeled chair in and out, especially into the shower. Helen also wanted her hair washed. We had a shower chair. It was all very fraught.

On one occasion, after a shower, she wrote, “That was horrible.” I agreed, and I laughed. She laughed. Of course, she didn't actually laugh because she couldn't. But I knew that she was laughing inside, and she knew that I knew, and we laughed more. You live on scraps of emotion and the understanding of 50 years.

Caring was now a full-time, 24/7 activity. It was impossible to continue without a change, and the family organised a roster. I dealt directly with Helen’s physical needs, while the family washed, ironed, cooked, mowed the lawns, got the groceries, and cleaned. I was getting no regular sleep, only catnaps, but I always had help to call upon during the nights.

By now, she could not lift her feet, and we had to push and slide her across the carpet. In the small hours of one morning, the emotional dam broke, and our eldest daughter raised a tear-stained face and said, “Dad, I can’t do this anymore.” She was caring past her limit. Her mother was a shadow of her old self, almost a rag doll being manipulated through the days in the hostile environment of a home not designed for complete hospital-level care. We needed help.

Making the decision

Moira came from Motor Neurone Disease NZ. We were anxious about the meeting — dear Helen needed to agree to move into a rest home. We had lived in this house for 45 of our 50 years together, and we all knew how much she wouldn’t want to leave. Moira spoke gently with her and the family for over an hour. Then came the critical suggestion: “It might be better if you moved into a new home where you can be better cared for.”

It was such a poignant moment. Helen was so brave, and she nodded. We were all so relieved and so proud of her. She knew what she was facing and faced it with confidence.

The staff at the rest home were wonderful. It was important never to give in to the thought that this was all a hopeless endeavour. It was important always to maintain the view that the latest setback was the last. In this way, you could continue to care with love and positivity.

I remember discussing two positives with the staff as Helen settled in. They had a big van for outings. I asked if the wheelchair could fit, and I asked if we could both go to the seaside and maybe buy an ice cream. “Yes, of course.”

Showering would no longer be “horrible” and not restricted to once a week. They joked that she could enjoy a shower every day if she wished. A bright spot here was that one of our children discovered that she loved watching videos. She could watch without tiring herself. She would write “My Fair Lady” with a small smile—a wonderful respite.

Such were our bright outlooks, but we didn’t realise that only five weeks were left. We never made it to the seaside, and she had just one shower. Life had become too hard. She could barely move and was constantly breathless. These were the worst of times.

The final weeks

The end was close but was starkly brought home to me when one of the children came to the front door, holding a box and said, “Mum asked me to take it home”.

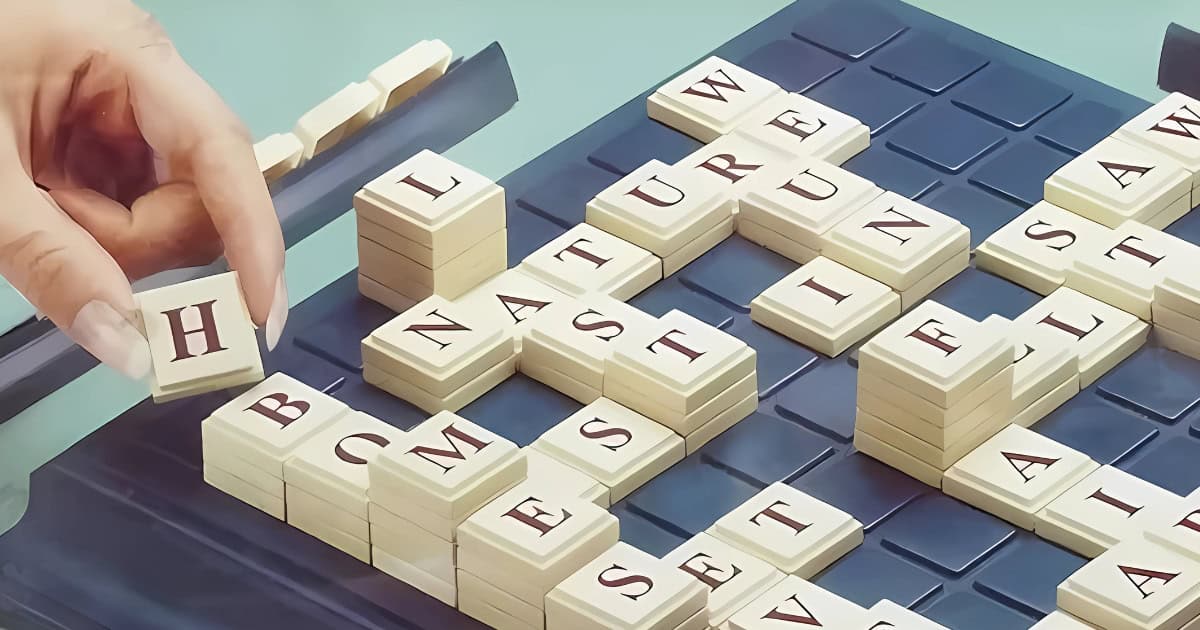

For 30 years, we played a board game called Upwords — a word-building game she absolutely loved. We played every day. “The game, the game, the game,” she would call out, and I knew it was time to set it up. It took about an hour. We kept notebooks of results — every score, every move, winning and losing margins, records set. When she moved to the rest home, she insisted we take Upwords with us. After all, we could still play every day — maybe even twice a day.

We managed half a game before she became too tired, and I placed the box on top of her wardrobe. When she later asked our daughter to take it home, I knew the end must be near. She was acknowledging that she would never play again. “The game, the game, the game” was stilled.

She was now writing “I’m dying.” What did that feel like? We couldn’t know; we felt her loneliness. We grieved but could not help.

Helen was breathing fast, short gasps. I called the nurse. She was going to be given a relaxing medication, but the question was whether she wanted it. She didn't know what to say and looked at me for guidance, our last communication. She turned her head to one side and breathed for the last time.

It was over.

At her funeral, I described her experiences as contained within a large sphere—a space filled with all her capabilities, loves, aspirations, laughter, wise advice, and everything she enjoyed. As the months passed, the sphere slowly shrank, and each part of her life slipped away, never to be appreciated again. Ultimately, she became just a dot at the centre—bereft of all she had been and achieved—but never, ever forgotten.

This is the conclusion of our experience. I write in the hope that it may resonate with others and perhaps offer guidance or comfort to those facing similar situations.

In memory of Helen.

Keith Thomas