Finding laughter and joy in the darkest places

Awareness, Personal Stories

28 May 2024

Sam Stuchbury

Tomorrow’s a new day. There’s light at the end of the tunnel. You can’t stop the waves of life, but you can learn how to surf. Clichés often contain a kernel of truth, which is probably why they gain traction in the first place. And over the past 18 months clichés have made an appearance in my life more often than before. Gone, but not forgotten. Their memory lives on. Rest in peace

…

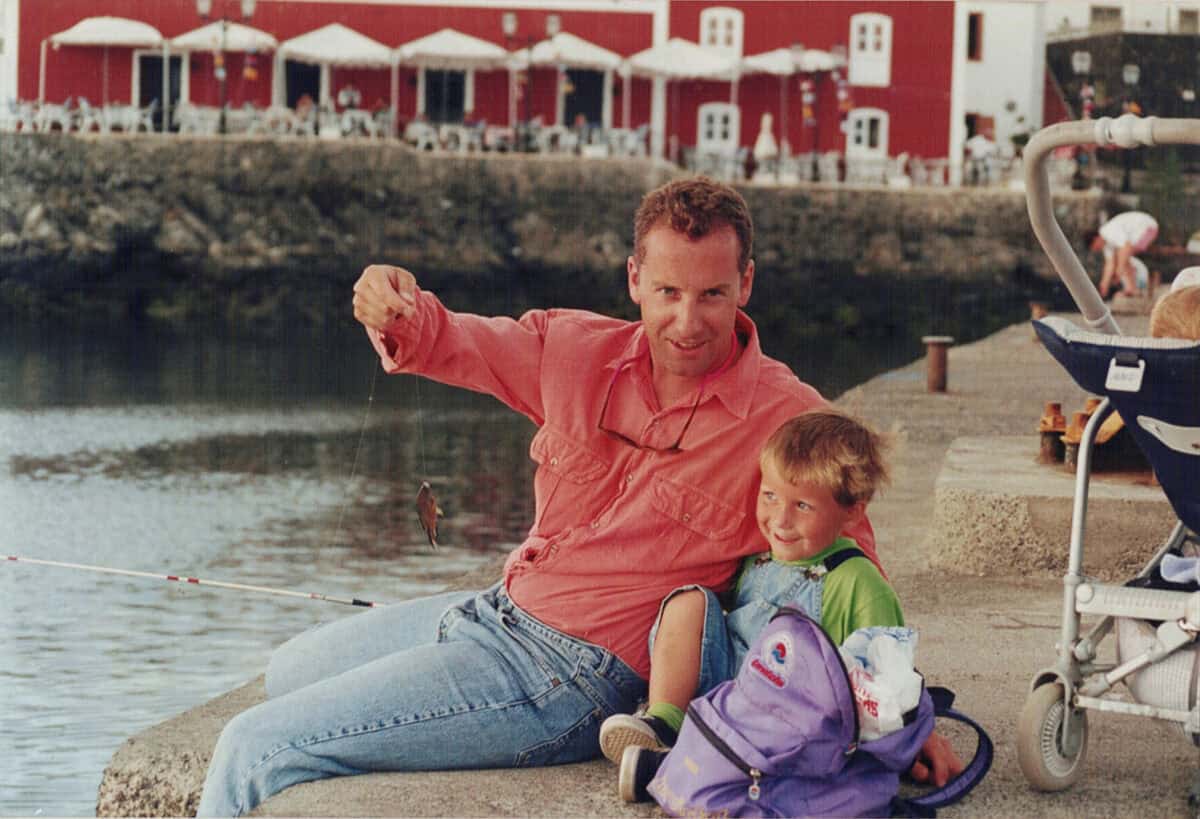

On 7 October 2022, my father, Kevin Stuchbury, at the age of 59 was diagnosed with motor neurone disease (MND). He passed away in December 2023. And his fight with this brutal disease was, well, brutal, but he faced it with such kindness, strength and humour that it’s a story worth telling. After Dad’s passing, MND NZ reached out to me for a perspective on dealing with MND as a son, not as a patient. To offer any advice that might be useful to a younger connected family member. So here we are.

Our family has invariably turned to humour to deal with life's challenges, with my dad leading from the front. However, this became much harder to do when I received a call from my mum that October. In the 18 months leading up to the diagnosis, Kev had progressively been experiencing a tickling throat after eating, as well as some light tremors. At the time, this was put down to allergies.

Kev was a big guy, just all-around big. Over 6 feet tall and as solid as a rock. He was affectionately called Homer, after Homer Simpson — so when coughing meant putting away a donut or a flaky pastry became too much to handle, eyebrows were raised. On reflection, I suspect Dad knew something was pretty wrong.

With a cocktail of various allergy medications making no difference, and a trip to an ear, nose and throat specialist not providing any answers, Dad was referred to a neurologist. That’s when our lives changed. It took just a 20-minute consultation for our family’s world full of life and joy to come buckling at the knees.

‘Kevin, I am 95 per cent sure you have motor neurone disease,’ the neurologist explained. Later, my mum told me that, after Dad had left the room, the neurologist had told her that he suspected Dad had around two to three years of life remaining. The doctor then began to cry, then he hugged my mum. ‘It never gets easier’.

The thing with MND is you’re fighting, but not really fighting for a win. There is no predictable path, as each presentation of MND is different, so you are overwhelmed by unknowns. Ultimately you have to ride the predictability of the outcome, while accepting the unpredictability of the journey. This may sound unhelpful, but it is an important truth.

In those early days, the scariest thing was the unknown. Including knowing how to try to exist yourself in this new warped normality. I remember going fishing with a friend just a week after the diagnosis. When we got home, I looked at one of the photos we’d taken. There I am, sitting on a kayak holding a snapper, smiling. I remember looking at that photo and wondering, ‘Is that okay? Should I be allowed to do that right now?’ Behind me in the photo is a rainbow, a legitimate fucking rainbow. Nature saw my legal snapper as a magical moment, to be celebrated by a pot of gold; I saw it as an extremely confusing keeper.

Confusing fishing trip

Reflecting back, I now see such moments of escape as crucial to our journey. It was hard to do something for yourself, or to try to do something normal as a family. It took way more effort than it should have. At the time I sometimes felt guilty, but now I see it as healing. The day after my dad’s diagnosis, I also began to exercise, somewhat obsessively. The jury really isn’t out on positive effects on mental health, and so I began to exercise every morning, without fail. This is the single most important ritual for my mental health during what were, without a doubt, the hardest 18 months of my and my family's life.

Mum and Dad met aged 15 in the UK. They went to school together, childhood sweethearts. We didn’t come from lots of money, or a particularly beautiful place — south-east London. But they made life beautiful. Camping trips, a house of laughter, love and good taste…. To this day we have Live. Laugh. Love. on the wall at our family home.Their relationship just worked, and through Dad’s MND journey their relationship only deepened. Still, it was hard to see Dad change, but equally so to see mum bear the weight of caregiving and loss.

Tasteful fine art in family home.

Mum has a directness and openness that makes nothing too awkward to talk about. Through the journey, this openness between family members was really important. And it was okay to laugh. About midway through Dad’s journey, he began to lose strength in his legs and had fully lost his voice, and my parents would go camping. One day I joined them there and went for a walk with Mum. “Have you thought about the funeral?” asked Mum. “A bit early, but mmmm, yeah a bit,” I replied. Being a foodie Mum continued: “I was thinking about a cold buffet for the funeral, and about what I would say.” “Let’s wait a few months before we dig into the funeral buffet plans, eh? It feels a bit premature.” I knew my mum was half-joking to get a reaction out of me. I also knew she was probably mulling over whether to go with sausage rolls or mini savouries. Probably both.

These constant open conversations were invaluable, even if sometimes a little startling. Nothing was off the table; we could say what we liked to each other. My partner Hilary’s unwavering openness and support also gave clarity to confusing emotions. However, she was losing a father figure, too; Hils was close to Dad, and it was important to remember that. She knew what I was thinking before I said it, and we were able to share our deepest concerns without judgement. It brought us closer, even when we thought we couldn't get any closer.

We protected Dad from the more direct conversations, though. He chose to not discuss the end of life, and instead focus on the days he had. We respected that.

The strength my dad showed throughout the illness will stay with me forever. I guess you never really know how people will respond to a diagnosis; we were lucky with the inner balance Dad found. Of course, he had down days, but after the initial shock of diagnosis he showed optimism, humour and strength. Each new operation, medication or device was just another milestone to overcome. Each new doctor was just another audience for a joke, and each new day was a new day to embrace. It was gut-wrenchingly admirable.

I am not sure where he found this strength; he told Mum he just managed to compartmentalise and not think about the bad stuff that much. It is what it is. And we let him choose how he wanted to deal with it; we would support him whatever.

After having a PEG installed — a feeding tube inserted directly into the stomach through the abdominal wall to avoid choking and weight loss — Dad would feed liquid food through the tube. On our last big holiday together, to Noosa, I fed Dad a glass of whiskey through his PEG, and then we watched Tom Hanks at his best – Saving Private Ryan. It was nice to not need to always talk about MND, but just exist with each other, even if he couldn’t speak.

As Kev’s MND progressed, his physical symptoms got more severe, particularly his trouble breathing. A cold quickly developed into pneumonia and difficulty breathing, and, although he insisted he was fine, my mother called an ambulance, which whisked him away to A&E. What followed was probably the second hardest period of the journey, after the initial diagnosis.

Dad spent three weeks in the hospital, mum sleeping by his side on the floor every night, my sister and I taking shifts to be with him. Although New Zealand’s perception of the medical system is that they couldn’t organise a piss-up in a brewery, or a blood test in a hospital. Our experience of the system was very good. Doctors, nurses and physios went over and above with what was required, MND NZ organised specialists, the respiratory ward was faultless. Sure it was bleak — the food was bad, the chairs were literally held together with duct tape, and seeing Kev on a ventilator was obviously confronting. But the team was great, and they did all they could.

After one particularly difficult night in the hospital, covering for my mum, I had to press the emergency button to get help. Dad was having one of his breathing attacks. What followed was something my mum was used to, but was really new for me. Three hours of heart-wrenching panic attacks, clearing choked airways and calming Dad down. My instinctive reaction was to try and lighten the mood, which I think Dad appreciated. One nurse decided to refer to Dad as ‘Daddy’, not really getting the slightly erotic innuendo. Dad did. He shot a glance and a wink to me even as he struggled to breathe.

Those days were tough. One evening his airways were so blocked that they had to be cleared with 20-centimetre-long suction tubes. My sister, mum and I all stood by the bed and squeezed hands. At one point, I just stepped into the ward toilet, cried for about 20 seconds, heard the commotion down the hall again, wiped away the tears, and went back into the room. But Dad got through it, so should we.

Moments later, he picked up his iPad and typed ‘thank you’ to the group of doctors, and proceeded to smile and flex his bicep to show he was feeling strong now. It was moments like this that I actually found the hardest. Not the trauma of the illness, but the moments you see the magic of the person you love, and the prospect of losing that.

Back home, he was weaker and now using a BiPAP airways machine at night and for hours during the day. At this point, about a year into the disease, we had all come to a point where we just wanted to spend time with each other and enjoy the time we had. However, I found myself constantly worrying how it would end, which I assume is common for MND families. I wondered in what state Dad would leave us, and how his eventual passing would happen. I would try to stop thinking about it, but on the long drives, the boring work meetings or the long nights I would wonder. Ironically, in spite of all that thinking, I never would have guessed how it would end.

The last night I spent with him didn’t feel like it would be the last. My sister and my mum wanted a break to go and feast on some refined ‘culture’, so they booked tickets to Sam Smith’s 2023 GLORIA tour. I was to cover for Mum at home for the evening. Dad was positive; weak, but positive. We stayed up and watched a film. Dad usually went to bed by about 8, but that night he was keen to push on. He gave me his laptop with the TAB page open, so we bet on the dogs; we laughed and cheered at the screen, Dad raised his arm. It was really nice. When Mum got home around 11pm, she was surprised to see Dad up, and asked him whether he was not tired. He nodded, but I knew he probably was; he just didn’t want the day to end. Those little moments that seem so normal and unexceptional are the moments I value now. Winning $5 on Quick Paws McGraw with Dad by my side felt like the biggest payday in history.

By this point in the journey, we were preparing — and planning and worrying — for Dad to lose more use of his bodily function, and eventually become bedridden. Still, we assumed we had some time on our side. But at 8.30 on the following Wednesday evening, my phone rang; I was already in bed. When I saw my mum’s name, I knew something was wrong: for the past year a phone call from my mum always made my heart skip.

Through tears and heavy breathing, my mum brokenly said, ‘Dad has just died. I just tried to do CPR on him in the chair. The ambulance is here.’ My head spun; I called Hilary into the room and tried to stay calm. It was the longest 30-minute drive of my life to my parents’ house in Whangaparaoa. What eventually caused his passing wasn’t a further drawn-out, long goodbye, but instead a suspected pulmonary embolism in his lung, caused by scar tissue from his pneumonia. It lasted all of a few minutes. Mum and Dad were at home, watching Below Deck. I guess reality shows can make you cry.

We sat in the lounge with my sister, grandmother, Hilary and wider family. We dealt with the following weeks together. We even planned the funeral buffet; the time was appropriate now. Even in the bleakest of funeral moments, it felt like Dad was there trying to lighten the mood. After we had loaded Dad, in his coffin, into the hearse, we stood back so the young chap from the funeral home could lower the door, he slammed the boot revealing the back of the car. It seems this small thriving Whangaparaoa business had invested in a small, probably unnecessary, piece of marketing, a customised number plate, ‘RSTNPC’. Through tears, Hilary and I smiled; I’m sure Dad was doing the same.

Nothing can prepare you for the final loss of a parent. It’s an odd melting pot of deeply confronting sadness, shock and tiredness. I was overwhelmed by how tired the sadness made you. However, one unexpected emotion was there for me. Happiness.

Looking at photos, sharing stories, talking about Dad, it didn’t add to the sadness; it lightened it. It made me happier. The memory of Dad and his life wasn’t tainted by his disease, as I had feared; it couldn’t and wouldn’t ruin anything to do with his well-lived life. MND was an unfortunate and premature end to his life, but in no way defined it.

MND is a brutal disease, and initially it’s hard to find positives. Ironically, I think in some ways the one thing it does give you is time. He wasn’t taken suddenly in a crash or from a heart attack. We had time to know the end was coming, to grieve, and come to terms with it, somewhat, with him. A parting gift from him was the strength and positivity he showed, which has stayed within me and my family. Now those stressful days at work seem a little less stressful, those annoying people you meet just become funny, you love your partner deeper than you thought you could, and you’re happier with a life you were already happy with. It gives you perspective on what’s important. It’s all about perspective.

Thank you to MND New Zealand, the Taikura Trust, the hard-working medical team at the hospital, and the nurse who called Dad ‘Daddy’. These services made the impossible possible for us, and we are forever grateful. And Nurse ‘Daddy’, you brought a smile to a day that was frowning. Finally, thank you to all the friends, family, and colleagues who offered support, meals and txts over those 18 months; my family and I couldn't have gotten through it without you. I sit here today with relief that that part of our lives is over, but happiness when I think of Dad and his life. The grief will probably never completely leave, but the joy of Dad and his spirit will definitely stay.

Reading back what I have written of our journey, I tried to find the main piece of advice to take away from the experience. I guess it might be that even in the bleakest of circumstances make room for the joy, laughter and normality. And when they do appear, don’t feel bad about indulging in them. Because what happens after you die on a Wednesday? The bins get picked up on a Thursday. In the nicest way possible, life goes on. Although that may sound heartless, to me it’s a commentary on how strong we are as human beings. We find a way through. Those who are sick, and those who are not. While you’re navigating the journey, be open to the good moments. And in the end our families and those we lose wouldn’t want us to dwell on the past, but instead embrace the future. Love, laugh and — don’t forget — to live.

Motor neurone disease (MND) is a fatal, rapidly progressing neurodegenerative disease. There are around 400 people living with MND in NZ at any given time, with on average 2 people dying each week and 3 people receiving a diagnosis.

The incidence rate of MND in NZ is higher than the rest of the world – researchers are trying to find out why so we can change it. Motor Neurone Disease NZ is the only charity focused on improving quality of life, funding

research and campaigning for people affected by MND in NZ. MND NZ is raising funds to support promising research that's happening here in Aotearoa New Zealand, as well as supporting global research efforts.

To find out more about what support and information is available, please head to mnd.org.nz